What is Pudendal Neuralgia?

Pudendal neuralgia is just one of many possible causes of pelvic pain. An accurate diagnosis can help target treatment, so clarifying the typical symptoms can help you and your clinician get to the source of it. This article is more detailed than some, and is intended to help you understand the specifics of pudendal nerve injuries. Knowledge of the structures involved will help you understand and manage your own symptoms and what treatment possibilities exist.

As with all nerves, pressure or tension decreases blood supply, and will, over time, contribute to poor health in the nerve and increased sensitivity. Repeated compression in sport, particularly with high muscle tone in the pelvic floor muscles, can cause the nerve to fibrose and thicken. Local ligaments can thicken as well, leaving narrower passages for nerves. Our sedentary jobs, which involve prolonged sitting, adds considerable pressure to the pudendal nerve and can contribute to further irritation of the pudendal nerve.

Pain in this nerve has been commonly described in cyclists and is often called “cyclist’s syndrome”. This pain is not exclusive to cyclists and can arise from a variety of other sports and activities, including weight lifting. Cycling is thought to compress the nerve, whereas weight lifting demands considerable support from the pelvic floor muscles. In a full squat, the pelvic floor muscles are stretched, and may result in a tension mechanism causing injury to the nerve. Childbirth also poses a risk to the nerve, especially with a large baby, or a delivery needing forceps or vacuum. Pelvic surgery very occasionally causes injury to one of the branches, as can direct trauma to the pelvis.

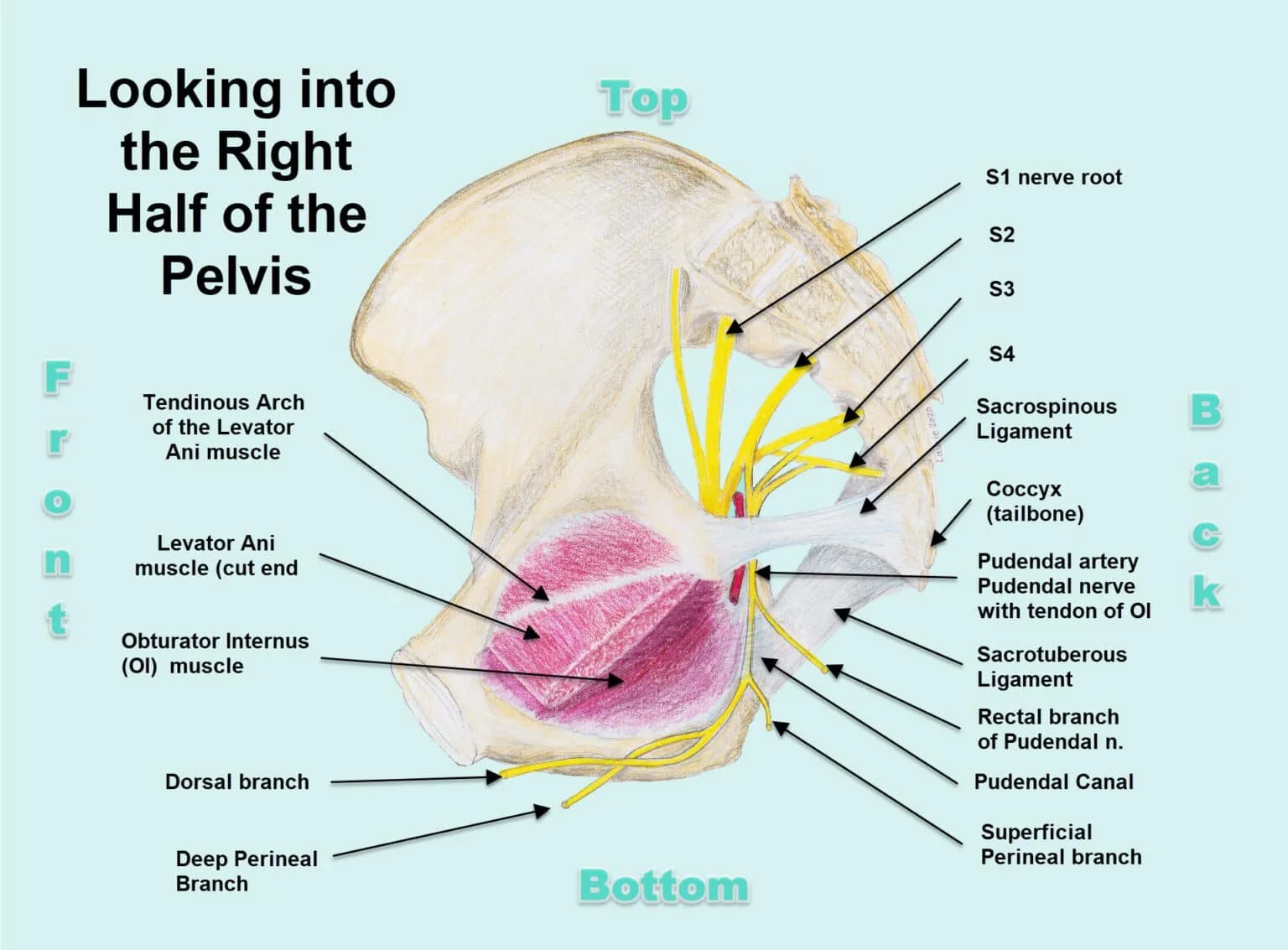

The pudendal nerve is made up of some of the lowest nerve roots from the spinal cord. Branching directly from the spinal nerve roots ( S2, 3, and 4) on the inner surface of the sacrum within the pelvis, the nerve exits the pelvic cavity under one of the hip muscles (piriformis, not shown in this image). It curves downwards between two heavy ligaments (sacrotuberous ligament and sacrospinous ligaments) to go back into the pelvic cavity1.

In the image, you can see the nerve passing under the sacrospinous ligament with a portion of the pudendal artery. As the nerve re-enters the pelvic cavity, it passes under tough connective tissue covering a muscle on the inner wall of the pelvis (obturator internus muscle). This forms what is called the pudendal canal (Alcock’s canal). Each twist and turn of the nerve is a potential site for it to be compressed.2

Understanding pelvic anatomy can help you manage pudendal neuralgia.

If pain is truly originating from a part of the pudendal nerve, it will be in at least part of the nerve’s distribution area. The distribution area of the pudendal nerve covers the very central part of the pelvis 3,4. It divides into 3 main branches : the rectal, the perineal, and the dorsal (clitoral or penile).

The rectal branch supplies sensation to the skin in the area of the anus and motor control of the external sphincter.

The perineal branch divides and supplies the labia and vulva, as well as the outer third of the vagina in women. In men, it innervates the skin from the anus forward to the posterior part of the scrotum and the underside of the penis. For both sexes, it supplies many of the muscles in the base of the pelvis (pelvic floor).

The dorsal branch gives sensation to the clitoris and its hood, or the back of the penis and glans in men. The dorsal branch also gives motor power to the sphincters that are part of bladder control, and the ejaculatory mechanism.

It is worth noting that nerves have considerable variability between different people, and that there is overlap between adjacent nerve areas. No textbook diagram will exactly match you and your nerve layout.

Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia were developed in 2006 and include 5 key items:

pain in the pudendal nerve area, which may be superficial or deep in the anus, vagina and vulva / scrotum and penis, to the tip of the urethra

the pain is worse with sitting, since the nerve is less mobile and so is more vulnerable to compression

it does not wake the person at night

there is no loss of sensation (that would reflect a sacral nerve root problem, further up than the pudendal nerve, a different issue, with different treatment approaches)

it is resolved with a pudendal nerve block injection. This is a tricky criterion since an injection placed just a little off the target will anesthetize more than one structure and may give a false positive.

There are associated signs and symptoms as well that are commonly seen :

hypersensitivity, shooting or burning pain in this nerve’s distribution area

tingling pain

pain after ejaculation or bowel movements ( from tight local muscles )

pain worsening through the day

sense of a foreign body in the rectum or vagina

pain predominantly on one side

exquisite tenderness with (internal) examination of the opening of the pudendal canal

Many people respond well to exercises to reduce muscle tension in the pelvis therefore increasing the mobility of the nerve, and allowing better blood supply to it.

Physiotherapists teach specific relaxation techniques for the pelvic muscles, and encourage overall relaxation. It is usually coupled with internal techniques (vaginally or rectally) to help with muscle tension and sore points. Some patients use wands intermittently to manage acute episodes of pain. Posture and ergonomics are important considerations for reducing tension and pressure on the nerve as well. A pelvic physiotherapist will walk you through each of these points as they relate to your situation. Modifying sports equipment (bicycle seats for example) can help reduce symptoms as well. Milder or intermittent symptoms often resolve with these approaches in a few weeks. The longer a nerve has limited blood flow, the longer it will take to recover. Patience and keeping it relaxed are key. Very often, tension in the pelvic floor muscles goes together with a more anxious personality or a time of higher stress. We commonly see stomach upset, even IBS, headaches, and bruxism (grinding of the teeth) going with pelvic muscle tension. Meditation, deep breathing, and positive coping strategies to decrease the ‘wind up’ are important pieces of the clinical puzzle.

Physicians will often prescribe anti-inflammatory drugs as a first choice to try to settle the area 5. If the pain persists, your physician may consider prescribing an antidepressant or an anticonvulsant, both of which have been shown to be effective with longstanding nerve pain.

If conservative treatment is not successful over several months, injections of steroids are often tried, and are aimed directly at the area. Injections into the base of the tailbone can be used to ‘reset’ the painful nerves with doses of anesthetics or other medications. They may be used to help pinpoint and diagnose the nerve and specific area in trouble, allowing a more targeted approach if surgery is needed. Surgery to take the pressure off of the nerve is a possible option, and in the past couple of years can include the implanting of a pump under the skin to give medication to the nerve area via a small catheter6. Other investigational approaches include IV infusions over hours and even days of very low doses of anesthetic that is effective in calming the nervous system. Some physicians are trying radio waves to heat and cool a small part of the nerve, decreasing its ability to sense pain5.

In general, understanding what you may have injured, and how you can best take care of it is the first and most important goal. Finding approaches (perhaps several at once : exercises, meditation, medication, acupuncture) to help the pain settle so that you can function and do your part is key. Progress is often slow and gradual with pudendal neuralgia. Have patience. If more help is needed over weeks and months, your physician and pelvic physiotherapist are there to guide you.

This video about pudendal neuralgia may also be helpful. Enjoy!

References:

1. Williams PL and Warwick R. Gray’s Anatomy 36th Edition, Churchill Livingstone, 1980. p1115

2. Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, Amarenco G, Lefaucheur JP, Rigaud J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol. Urodyn. 2008;27(4):306-10

3. Beco J, Pesce F, Siroky M, Weiss J, Antola S. Pudendal neuropathy and its pivotal role in pelvic floor dysfunction and pain. In: ICS/IUGA conference. 2010. p. 0-12.

4. Rojas-Gómeza MF, Blanco-Dávilab R, Tobar-Roac V , Gómez-González AM , Ortiz-Zablehe AM , Ortiz-Azuerof A. Regional anesthesia guided by ultrasound in the pudendal nerve territory. Rev. colomb. anestesiol. vol.45 no.3 Bogotá. July/Sept. 2017

5. Lemos, N, and Pelvic Health Solutions. Pudendal Neuralgia and Other Intrapelvic Causes of Neuropathic Pain. (course) on Embodia:https://www.embodiaacademy.com (2018).

6. Li, A.L.K., Marques, R., Oliveira, A. et al. Laparoscopic implantation of electrodes for bilateral neuromodulation of the pudendal nerves and S3 nerve roots for treating pelvic pain and voiding dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J 29, 1061–1064 (2018).