Visceral Manipulation for the treatment of Diastasis Rectus Abdominus

By Florence Bowen, DOMP

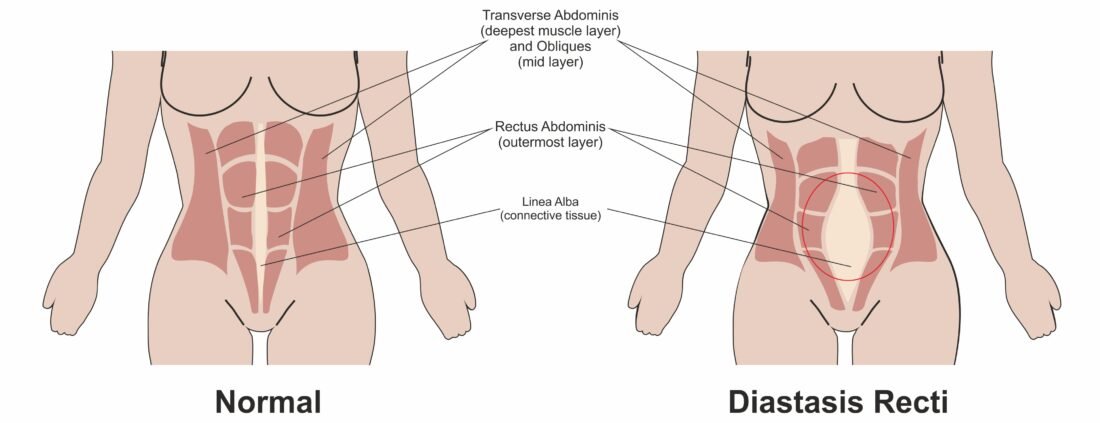

The condition diastasis rectus abdominis (DRA) is defined as the compromised integrity and function of the abdominal wall due to the separation of the two rectus abdominis muscle bellies from the linea alba (Noble, 1982). In other words, DRA is the overstretching, thinning and widening of the linea alba, the band of tissue between your six-pack muscles. Often DRA looks like a coning or doming of the abdomen during activities that increase abdominal pressure like, sneezing, coughing, performing a sit-up or straining on the toilet.

What is important to recall is that diastasis rectus abdominus is a normal response of the body to the growing uterus during the later stages of pregnancy. Around the fourth month of pregnancy the uterus moves from the pelvis and into the abdomen. This growth of the uterus creates new tension on the abdominal wall and is the driving force of the expansion through the front of the belly.

Mota, Pascoal, Carita, and Bø (2015) reported that at 35 weeks of the gestational period, 100% of their recruited population had DRA.This means that DRA is not a condition you can prevent during pregnancy, but rather its a condition that needs to be managed during pregnancy and then rehabilitate in the postpartum period.

Mota et al. (2015) observed that at the immediate postpartum period, 6 to 8 weeks, DRA was observed to persist in 52% of women, 53.6% of women at 12 to 14 weeks postpartum, and in 39.3% of women at six-months postpartum.

These stats tell us that for a lot of postnatal people, there is a natural healing process during those initial weeks postpartum and any DRA is resolved without any type of assistance.

The first eight to twelve weeks postpartum are referred to as the “critical healing period” the greatest amount of healing or natural restoration of the abdominal wall takes place during those weeks. Beyond the critical healing period the natural resolution of DRA has plateaus, without any type of intervention the ‘closing of the gap’ stalls.When some degree of separation persists past the initial twelve weeks period, often exercise based rehab is suggested to ‘close the gap’ further.

The standard and most conservative intervention for the rehabilitation of the abdominal wall remains to be deep core training. If someone does not respond to deep core training, meaning they cannot generate tension through the abdomen and they are suffering from urogynecological dysfunction or pain due to diastasis rectus abdominus, surgery is sometimes warranted.

“With little evidence to guide DRA recovery, are there any other approaches or modalities that might help when surgery feels imminent?”

This is the question that I asked myself as an Osteopathic student who was teaching deep core training in postnatal classes throughout the city of Toronto. I was curious to explore how manual Osteopathy might affect DRA in postnatal women. When it came to choosing a thesis topic in my last year of Osteopathic schooling, I had no problem deciding.

I conducted my own quantitaive research which explored the effects of four global manual osteopathic treatments on the distance between the two six-pack muscles, also known as ‘inter-recti distance’ (IRD). Each subject was either at or just beyond the critical healing period and although it was a small sample size, the results were very encouraging. Osteopathic treatment significantly decreased IRD above, at and below the umbilicus at rest.

From my research, a large portion of each treatment, but not the only manual approach applied, consisted of myofascial mobilization and visceral manipulation (VM). VM involves the gentle but specific placement of manual forces to encourage the mobility and movement of the viscera. The soft mobilization of the fascia and the ligamentous structures that suspend or connect the viscera to each other or the abdominal wall can potentially ameliorate the functioning of the organs.

Since completing my research and defending my thesis in 2019, new research has emerged which investigated the effects of VM alone on DRA. Physiotherapists, Kirk and Elliot-Burke, gathered and reviewed the charts of three patients who had received primarily VM in their first four sessions. At their initial appointment, each patient was identified as having diastasis rectus abdominus and IRD measurements were taken using finger widths above, at and below the level of the belly button. Across all three cases, significant decreases in IRD were observed across all sites and were sustained months later.

Why would VM impact DRA? That is a loaded question! In short, many of the viscera of the abdomen blend and are continuous with the fascial lining of the abdominal wall. Fascia is a form of connective tissue that is web like in nature, it surrounds and encases the muscles, bones and organs of the body. The fascia that surrounds and encloses the organs, like the kidneys for example, blend with the fascia of the transverse abdominis, which is directly connected to all your ab muscles. The abdominal viscera like the large intestines, small intestines, kidneys and stomach must temporarily relocate during the later stages of pregnancy to make space for the uterus. It is expected that the organs find their way back to their “normal” resting place postpartum. However, that is not always the case, and restrictions from the viscera can create tension or pull on the abdominal muscles which will negatively impact their function. This might feel like difficulty activating or recruiting your deep core.

Much more research is needed to ameliorate and guide the future care of DRA in the postnatal population. However, the benefits of seeking VM to help with an existing DRA are plentiful. VM is a gentle approach and it is only one of the techniques used during a manual osteopathic treatment and if you have ever experienced it, very relaxing.

Interested in exploring VM as a treatment option for DRA, book in for osteopathy today!

References:

Benjamin, D. R., van de Water, A. T. M., & Peiris, C. L. (2014). Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy, 100(1), 1-8

Noble E (1982): Essential Exercises for the Childbearing Year. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin.

Mota, P. G. F., Pascoal, A. G. B. A., Carita, A. I. A. D., & Bø, K. (2015). Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Manual therapy, 20(1), 200-205.

Sheppard, S. (1996). The role of transversus abdominus in postpartum correction of gross divarication recti. Manual Therapy, 1(4), 214-216.